If you are an individual investor that usually buys bank certificates of deposit, right now you may want to compare against a US Treasury bond of similar maturity. Treasury bond rates are traded constantly, but this Vanguard brokered CD page can provide a rough idea if they are worth a closer look (even though their brokered CD may or may not be the best CD rate available). Again, this screenshot is already out of date:

If you are an individual investor that usually buys bank certificates of deposit, right now you may want to compare against a US Treasury bond of similar maturity. Treasury bond rates are traded constantly, but this Vanguard brokered CD page can provide a rough idea if they are worth a closer look (even though their brokered CD may or may not be the best CD rate available). Again, this screenshot is already out of date:

Right now, they are pretty close for many maturity lengths. For example, let’s take a 1-year CD paying 3% APY and a 1-year Treasury bond paying 3%.

(Note: This may not be true by the time you read this. Here are the current Treasury bond rates. In the last two weeks alone, the 1-year Treasury has ranged from 2.79 to 3.21%. In 2022 alone, the low was 0.38%.)

An important consideration is that Treasury bonds are exempt from state and local taxes. This can make the Treasury bond significantly more attractive to some folks, even if the initial rate is the same. This assumes you are investing in a taxable account (not tax-sheltered). US Savings bonds are also exempt from state and local taxes.

For example, let’s say you are a single resident of California with a taxable income of $80,000 annually. Any easy way to compare the rates is by using a calculator like this Fidelity tax-equivalent yield calculator. Using the example income, it will find that your marginal tax rates are 22% Federal and 9.30% State (CA). I am assuming no local tax rates from your city or county.

What matters in the end is what you are left with after taxes. As such, the calculator supplies the following chart:

For this example person, a Treasury bond earning 3% will pay the same after-tax interest as a bank certificate of deposit paying 3.44%.

Here is a rough check on my part:

$10,000 * 3.44% * (1 – 0.22 – 0.093) = $236 in annual interest, after taxes

$10,000 * 3.00% * (1 – 0.22) = $234 in annual interest, after taxes

I suspect the minor difference has to do with the way that bond yields are quoted for Treasury bonds. This is also why the corporate bond yields are different from the CD yields even though they are subject to the same taxes.

Bond yields, except CDs, are assumed to be twice the semi-annual yield, as is the normal convention for quoting bond yields. CD yield is calculated as ((( corporate bond yield / 2) +1)² ) – 1

From the calculator fine print:

The calculator does not take into account:

– Reductions and limits on federal itemized deductions

– State and local taxes are not deducted from your federal tax rate. Depending on your personal situation, this may cause the resulting yield to be overstated.

– Federal alternative minimum tax (AMT)

– State alternative minimum tax

– Intangibles taxes levied by individual states

– Net Investment Income Tax

– Additional Medicare Tax

For practical purposes, I don’t sweat the minor differences. In order to actually buy many of these Treasury bonds at the time that you want and for the remaining maturity length that you want, you’ll have to buy them on the open secondary market. The available rates will change by the minute. Or, if you buy them as a new issue, you won’t know the rate at all as it is determined at auction. I mostly just want to know that the Treasury bond is preferable to a bank CD by an adequate margin. In this example, I would say that 0.44% higher annually is enough of a margin.

There are other wrinkles… if you don’t hold to maturity, Treasury bonds don’t offer the ability to withdraw early and only pay a preset interest penalty like a bank CD. You’d have to sell again on the open market, where you may lose (or gain) principal.

Armed with this information, you might create your own bond ladder using US Treasuries instead of a CD ladder. This is easy for an individual investor because you don’t need any skill to determine creditworthiness. Both US Treasury bonds and FDIC/NCUA-insured certificates of deposit are backed by the full faith and credit of the US government. (Municipal bonds don’t come with such a guarantee. Some municipalities are in better financial shape than others. I don’t buy individual municipal bonds for this reason.)

Here’s my quarterly update on my current investment holdings as of 7/8/22, including our 401k/403b/IRAs and taxable brokerage accounts but excluding real estate and side portfolio of self-directed investments. Following the concept of

Here’s my quarterly update on my current investment holdings as of 7/8/22, including our 401k/403b/IRAs and taxable brokerage accounts but excluding real estate and side portfolio of self-directed investments. Following the concept of

Updated July 2022.

Updated July 2022.

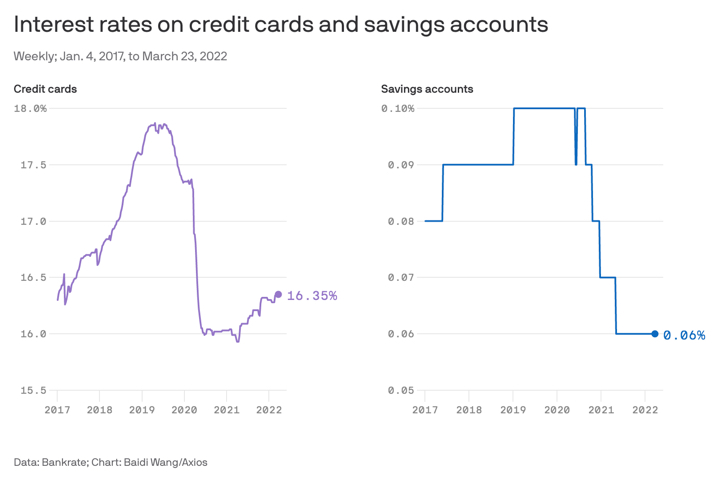

I’m going to wait a bit on my full May interest rate update, as I expect more rate changes early this week. Even the rates quoted below may become outdated quickly, but I wanted to point out certain rates at multi-year highs and also near the psychological 3% level. Here are a few examples as of 5/1/22:

I’m going to wait a bit on my full May interest rate update, as I expect more rate changes early this week. Even the rates quoted below may become outdated quickly, but I wanted to point out certain rates at multi-year highs and also near the psychological 3% level. Here are a few examples as of 5/1/22: I had to double-check the date when I received the press release for this product to make sure it wasn’t April 1st. 🤯

I had to double-check the date when I received the press release for this product to make sure it wasn’t April 1st. 🤯

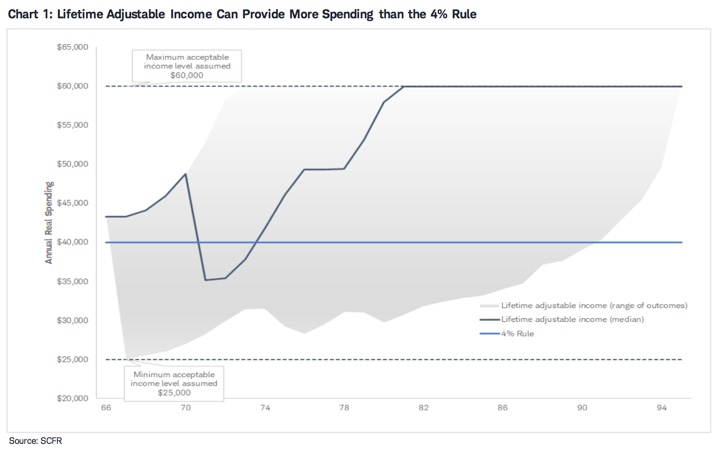

One of the perpetual debates in retirement planning circles is withdrawal rates, AKA how much monthly income can you take from a portfolio. Once you nail down a withdrawal rate and retirement spending target, then you get Your Number – how much you need to have saved to retire (after backing out Social Security and other income streams). It’s common to start with the static 4% rule, but that rule also includes some drawbacks. An alternative is a flexible withdrawal rule that adjusts based on market returns. When your portfolio grows, you can spend a little more. If it shrinks, you cut back a little. Sounds reasonable, right?

One of the perpetual debates in retirement planning circles is withdrawal rates, AKA how much monthly income can you take from a portfolio. Once you nail down a withdrawal rate and retirement spending target, then you get Your Number – how much you need to have saved to retire (after backing out Social Security and other income streams). It’s common to start with the static 4% rule, but that rule also includes some drawbacks. An alternative is a flexible withdrawal rule that adjusts based on market returns. When your portfolio grows, you can spend a little more. If it shrinks, you cut back a little. Sounds reasonable, right?

The Best Credit Card Bonus Offers – 2025

The Best Credit Card Bonus Offers – 2025 Big List of Free Stocks from Brokerage Apps

Big List of Free Stocks from Brokerage Apps Best Interest Rates on Cash - 2025

Best Interest Rates on Cash - 2025 Free Credit Scores x 3 + Free Credit Monitoring

Free Credit Scores x 3 + Free Credit Monitoring Best No Fee 0% APR Balance Transfer Offers

Best No Fee 0% APR Balance Transfer Offers Little-Known Cellular Data Plans That Can Save Big Money

Little-Known Cellular Data Plans That Can Save Big Money How To Haggle Your Cable or Direct TV Bill

How To Haggle Your Cable or Direct TV Bill Big List of Free Consumer Data Reports (Credit, Rent, Work)

Big List of Free Consumer Data Reports (Credit, Rent, Work)