To get the full return of any asset class, you’ll have to own it through the good times and the bad times. The good times are easy, but getting through the bad times requires deeper understanding and faith. You’ll usually hear this about holding stocks through their inevitable drops and crashes. But recently, many bond funds have dropped in value instead. Here’s a somewhat-reassuring chart from A Wealth of Common Sense comparing historical drawdowns between the S&P 500 stock index and 5-Year US Treasury bonds:

To get the full return of any asset class, you’ll have to own it through the good times and the bad times. The good times are easy, but getting through the bad times requires deeper understanding and faith. You’ll usually hear this about holding stocks through their inevitable drops and crashes. But recently, many bond funds have dropped in value instead. Here’s a somewhat-reassuring chart from A Wealth of Common Sense comparing historical drawdowns between the S&P 500 stock index and 5-Year US Treasury bonds:

Even so, having an investment that is supposed to be “safe” wobble 5% can still be worrisome. If Bank of America or Chase Bank announced tomorrow that their customers with balances above FDIC limits would lose even 1% of their excess deposits, there would be a huge crisis due to the perceived level of safety. A recent post by Longboard Funds makes an interesting claim: “…investors destroy more of their bond returns than their stock returns.”

This statement reminded of my surprise when reading this Bogleheads forum post on 11/14/16:

Bonds have been dropping every day [recently…]

Why? I thought they were a stable fixed investment.

S/he wasn’t alone, and I received a couple of similar e-mails, but I was struck that this person had been a member of the forum for over 2 years, made over 600 posts, and had previously detailed their asset allocation very specifically: “Brokerage account 65/35 | VG total Market 35% | VG total Intl 12% | VG small cap value 12% | VG Reit index 6% | VG Total Bond 35% | TSP Account 75/25 | C Fund 45%, S 15%, I 15%, G 25% | EE Bonds = Emergency Fund” Why did they buy all these things? No doubt from reading a lot of well-meaning advice from well-meaning people.

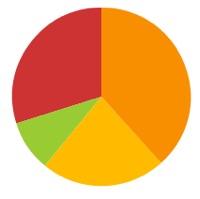

Bonds can certainly go down. There are also many different types of bonds. Longboard Funds put the two major risks of bonds into a nice graphic:

This won’t be a bonds primer, but instead I offer up how I try to treat bonds as part of my investment portfolio:

- I own bonds as a ballast and diversification element in my portfolio. (I also own stocks for inflation-beating growth.) I want relatively low volatility, but there will still be some based on credit and duration risk. I will take a little bit of each type of risk, but not too much.

- I also own bonds for modest income. I will be satisfied earning only modest interest rates that will roughly match inflation over the long run, and be happy if I earn 1% or 2% more than inflation.

- In order to take on a small amount of credit risk, I will stick to US Treasury bonds, investment-grade corporate bonds, and investment-grade municipal bonds.

- In order to take on a small amount of interest rate (duration) risk, I will stick to bond mutual funds with a relatively short duration (less than 5 years). The term “intermediate” could mean anything from 2 years to 10 years, so I’ll have to be careful. As a result, I will be less-exposed to short-term losses if interest rates rise quickly.

- In order to reduce the risk of any single bond default, I will own a large number of bonds inside a mutual fund or ETF. An exception would be individual US Treasury bonds as they all share the same, highest credit quality available.

Someone else may want to pursue higher bond returns and be willing to take on more risk. You could buy bonds from countries with shakier credit ratings. You could buy bonds from riskier companies. You could buy bonds with longer duration/maturities.

If you look again at that top chart, you can see several drawdowns of around 5% for a 5-Year Treasury. But what about a 20-Year Treasury, or 5-Year Junk Bonds, or international bonds from Argentina or Venezuela? It’s possible for some bond funds to drop 10% or more. If you are buying bonds because you think they are safe, stick to the safer bonds and realize that even they might still drop in price for a while.

Howard Marks released another

Howard Marks released another

As we close in on the end of the year, it is a good time to take stock of your investment portfolio. If you haven’t already, you should consider rebalancing your portfolio back towards your target asset allocation. Overall, this means selling your recent winners and buying more of your recent losers.

As we close in on the end of the year, it is a good time to take stock of your investment portfolio. If you haven’t already, you should consider rebalancing your portfolio back towards your target asset allocation. Overall, this means selling your recent winners and buying more of your recent losers.

If you get in a debate about owning index funds, Warren Buffett will likely be invoked as an example of successful stock-picking. A recent book called

If you get in a debate about owning index funds, Warren Buffett will likely be invoked as an example of successful stock-picking. A recent book called

This post is for the fortunate folks who may possibly exceed the often-quoted $500,000 limits for SIPC insurance ($250,000 for cash). The way this insurance works wasn’t necessarily obvious to me, and although it is often compared to the FDIC insurance of banks, there are many important differences.

This post is for the fortunate folks who may possibly exceed the often-quoted $500,000 limits for SIPC insurance ($250,000 for cash). The way this insurance works wasn’t necessarily obvious to me, and although it is often compared to the FDIC insurance of banks, there are many important differences.  I lent out my first $25 to a stranger on

I lent out my first $25 to a stranger on

The Best Credit Card Bonus Offers – 2025

The Best Credit Card Bonus Offers – 2025 Big List of Free Stocks from Brokerage Apps

Big List of Free Stocks from Brokerage Apps Best Interest Rates on Cash - 2025

Best Interest Rates on Cash - 2025 Free Credit Scores x 3 + Free Credit Monitoring

Free Credit Scores x 3 + Free Credit Monitoring Best No Fee 0% APR Balance Transfer Offers

Best No Fee 0% APR Balance Transfer Offers Little-Known Cellular Data Plans That Can Save Big Money

Little-Known Cellular Data Plans That Can Save Big Money How To Haggle Your Cable or Direct TV Bill

How To Haggle Your Cable or Direct TV Bill Big List of Free Consumer Data Reports (Credit, Rent, Work)

Big List of Free Consumer Data Reports (Credit, Rent, Work)