Here’s my (late) quarterly update on my current investment holdings, as of 1/23/22, including our 401k/403b/IRAs and taxable brokerage accounts but excluding a side portfolio of self-directed investments. Following the concept of skin in the game, the following is not a recommendation, but just to share an real, imperfect, low-cost, diversified DIY portfolio. The goal of this portfolio is to create sustainable income that keeps up with inflation to cover our household expenses.

Here’s my (late) quarterly update on my current investment holdings, as of 1/23/22, including our 401k/403b/IRAs and taxable brokerage accounts but excluding a side portfolio of self-directed investments. Following the concept of skin in the game, the following is not a recommendation, but just to share an real, imperfect, low-cost, diversified DIY portfolio. The goal of this portfolio is to create sustainable income that keeps up with inflation to cover our household expenses.

Actual Asset Allocation and Holdings

I use both Personal Capital and a custom Google Spreadsheet to track my investment holdings. The Personal Capital financial tracking app (free, my review) automatically logs into my different accounts, adds up my various balances, tracks my performance, and calculates my overall asset allocation. Once a quarter, I also update my manual Google Spreadsheet (free, instructions) because it helps me calculate how much I need in each asset class to rebalance back towards my target asset allocation.

Here are updated performance and asset allocation charts, per the “Allocation” and “Holdings” tabs of my Personal Capital account.

Stock Holdings

Vanguard Total Stock Market (VTI, VTSAX)

Vanguard Total International Stock Market (VXUS, VTIAX)

Vanguard Small Value (VBR)

Vanguard Emerging Markets (VWO)

Avantis International Small Cap Value ETF (AVDV)

Cambria Emerging Shareholder Yield ETF (EYLD)

Vanguard REIT Index (VNQ, VGSLX)

Bond Holdings

Vanguard Limited-Term Tax-Exempt (VMLTX, VMLUX)

Vanguard Intermediate-Term Tax-Exempt (VWITX, VWIUX)

Vanguard Intermediate-Term Treasury (VFITX, VFIUX)

Vanguard Inflation-Protected Securities (VIPSX, VAIPX)

Fidelity Inflation-Protected Bond Index (FIPDX)

iShares Barclays TIPS Bond (TIP)

Individual TIPS bonds

U.S. Savings Bonds (Series I)

Target Asset Allocation. This “Humble Portfolio” does not rely on my ability to pick specific stocks, sectors, trends, or countries. I own broad, low-cost exposure to asset classes that will provide long-term returns above inflation, distribute income via dividends and interest, and finally offer some historical tendencies to balance each other out. I have faith in the long-term benefit of owning publicly-traded US and international shares of businesses, as well as high-quality US federal and municipal debt. My stock holdings roughly follow the total world market cap breakdown at roughly 60% US and 40% ex-US. I also own real estate through REITs.

I strongly believe in the importance of “knowing WHY you own something”. Every asset class will eventually have a low period, and you must have strong faith during these periods to truly make your money. You have to keep owning and buying more stocks through the stock market crashes. You have to maintain and even buy more rental properties during a housing crunch, etc. You might own laundromats or vending machines or an online business. A good sign is that if prices drop, you’ll want to buy more of that asset instead of less.

Find a good asset that you believe in and understand, and just keep buying it through the ups and downs.

I do not spend a lot of time backtesting various model portfolios, as I don’t think picking through the details of the recent past will necessarily create superior future returns. Usually, whatever model portfolio is popular in the moment just happens to hold the asset class that has been the hottest recently as well. I’ve also realized that I don’t have strong faith in the long-term results of commodities, gold, or bitcoin. I’ve tried many times to wrap my head around it, but have failed. I prefer things that send me checks while I sleep.

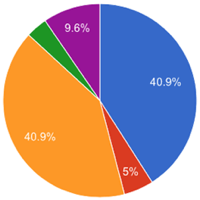

Stocks Breakdown

- 45% US Total Market

- 7% US Small-Cap Value

- 31% International Total Market

- 7% International Small-Cap Value

- 10% US Real Estate (REIT)

Bonds Breakdown

- 66% High-Quality bonds, Municipal, US Treasury or FDIC-insured deposits

- 33% US Treasury Inflation-Protected Bonds (or I Savings Bonds)

I have settled into a long-term target ratio of 67% stocks and 33% bonds (2:1 ratio) within our investment strategy of buy, hold, and occasionally rebalance. This is more conservative than most people my age, but I am settling into a more “perpetual” as opposed to the more common “build up a big stash and hope it lasts until I die” portfolio. My target withdrawal rate is 3% or less. With a self-managed, simple portfolio of low-cost funds, we can minimize management fees, commissions, and taxes.

Holdings commentary. I’ve been investing steadily for over 15 years, and the results have exceeded my expectations. There is ALWAYS something that looks worrying. Looking back, my best investment decisions were to NOT do anything different during times of stress. Maybe 2022 will have more such times. Ignore the noise, if you can.

I often wonder how I can teach my children such patience in investing, and that seems to be the hardest aspect.

Performance numbers. According to Personal Capital, my portfolio is up another +13.9% for 2021.

I’ll share about more about the income aspect in a separate post.

When talking about constructing an investment portfolio, you’ll often hear about diversification and buying low-correlation or non-correlated assets.

When talking about constructing an investment portfolio, you’ll often hear about diversification and buying low-correlation or non-correlated assets.

Perhaps it is because I somehow ended up buying $5,000 in gold coins a couple weeks ago, but I’ve been doing some reading about gold again. The stock market is at higher and higher valuations, while the Fed promises that interest rates will stay low for a long time. The real yield on TIPS remains negative, meaning that it is highly unlikely that any high-quality investment-grade bonds will beat inflation over the next decade. Is there really no alternative?

Perhaps it is because I somehow ended up buying $5,000 in gold coins a couple weeks ago, but I’ve been doing some reading about gold again. The stock market is at higher and higher valuations, while the Fed promises that interest rates will stay low for a long time. The real yield on TIPS remains negative, meaning that it is highly unlikely that any high-quality investment-grade bonds will beat inflation over the next decade. Is there really no alternative?

The Best Credit Card Bonus Offers – 2025

The Best Credit Card Bonus Offers – 2025 Big List of Free Stocks from Brokerage Apps

Big List of Free Stocks from Brokerage Apps Best Interest Rates on Cash - 2025

Best Interest Rates on Cash - 2025 Free Credit Scores x 3 + Free Credit Monitoring

Free Credit Scores x 3 + Free Credit Monitoring Best No Fee 0% APR Balance Transfer Offers

Best No Fee 0% APR Balance Transfer Offers Little-Known Cellular Data Plans That Can Save Big Money

Little-Known Cellular Data Plans That Can Save Big Money How To Haggle Your Cable or Direct TV Bill

How To Haggle Your Cable or Direct TV Bill Big List of Free Consumer Data Reports (Credit, Rent, Work)

Big List of Free Consumer Data Reports (Credit, Rent, Work)